Anglican Church remembers missionaries on New Guinea Martyrs Day

News

September 2 commemorates the Martyrs of New Guinea in the Anglican Church. Whom does this day honour and why? Ian Eckersley dives deep into the history and the incredible story behind this day, which is observed in the Anglican calendar worldwide, and has special relevance for parishioners in our Diocesan community.

Story Timeline

Saints and martyrs

- A maverick medieval mystic for modern times

- Anselm of Canterbury

- ‘Utterly orthodox and utterly radical’

- St Cuthbert – opening the door to the heart of heaven

- The man who would be king

- The saint and the sultan

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer: faith as unsovereign attention

- The life and legacy of Mary Sumner

- Mary, Mother of Our Lord

- Julian of Norwich: ‘all shall be well’

- Ugandan Anglican Martyr, Archbishop Janani Luwum

- Meet a saint for our times – Evelyn Underhill

- Benedict of Nursia

- Lady Eliza Darling – pioneering social reformer and evangelical Anglican

- Hildegard of Bingen

To the strains of the church choir, with 12 candles burning brightly and floral wreaths laid beneath a marble cross, St Paul’s Anglican Church, Ipswich provided the most moving celebration of New Guinea Martyrs Day yesterday.

Over 120 congregants crowded the pews of the historic brick and timber church to remember the names and stories of 12 faithful and heroic people who died for their faith during war time. Among those paying tribute was Mrs Mae Frame, the great-niece of Mavis Parkinson – the most well-known of the Brisbane Diocese’s martyrs. Miss Parkinson had been the parish’s Sunday school supervisor in the 1930s before moving to New Guinea as a missionary teacher.

The Martyrs – often called the New Guinea Martyrs – refer to 12 Australian, English and Papuan Anglican missionaries who were brutally murdered in several locations in August 1942 in then New Guinea (now the independent state of Papua New Guinea and the contested Indonesian provinces of West Papua and Papua).

Their deaths came largely at the hands of the invading Japanese forces, as well as by local New Guinea villagers who were under the influence of a local sorcerer who urged the locals to betray the missionaries’ hiding positions to the Japanese, or in some cases, to kill them.

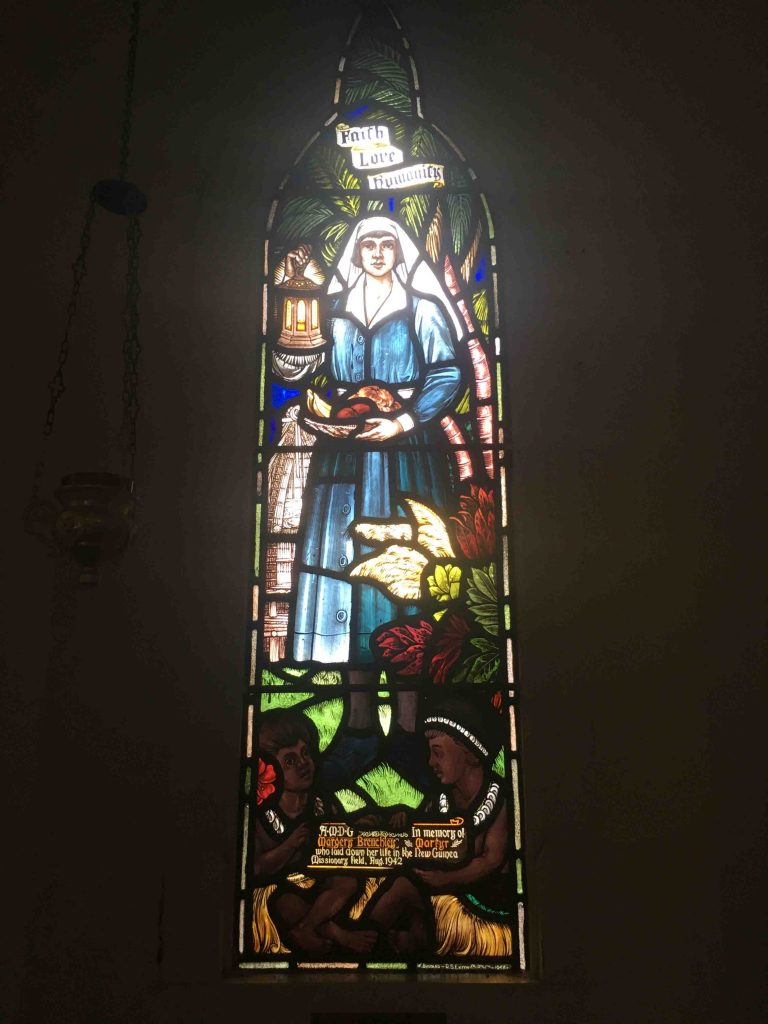

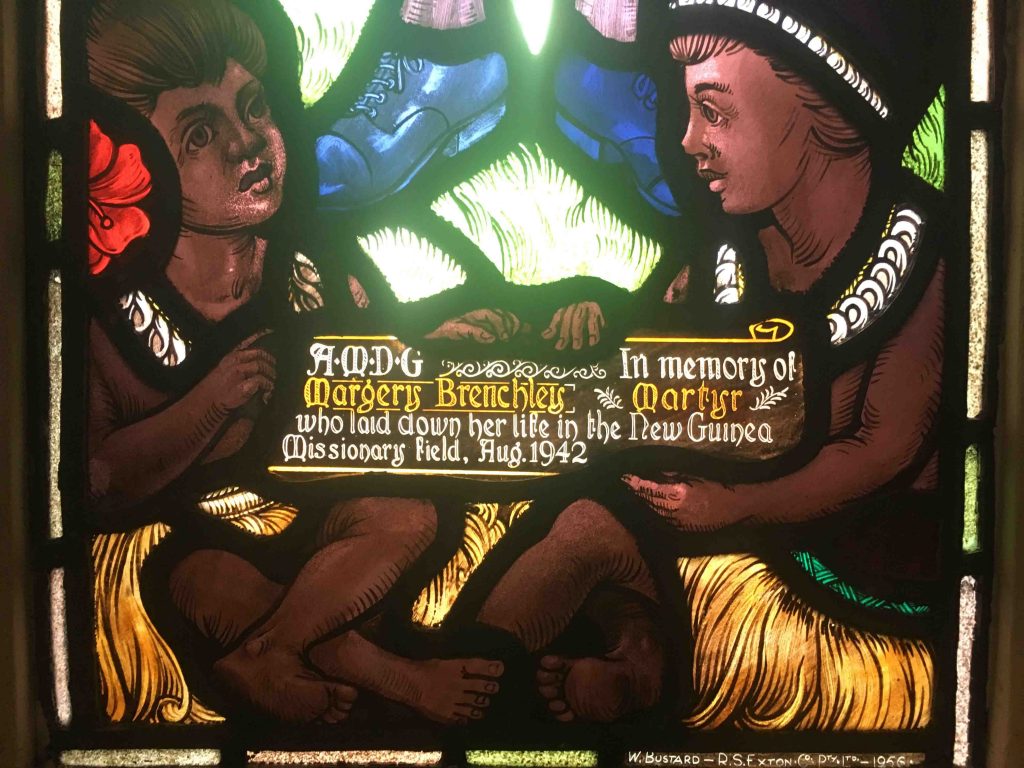

Four of the 12 martyrs came from the Brisbane Diocese. As well as Miss Parkinson from St Paul’s, The Rev’d John Barge had been a parishioner at St James’ Anglican Church, Toowoomba; Sister Margery Brenchley was a nurse from Holy Trinity Anglican Church, Fortitude Valley; while John Duffill, a missionary worker, originally came from Holy Trinity Anglican Church, Woolloongabba.

A stained glass window at Holy Trinity Church, Fortitude Valley, remember parishioner and martyr Margery Brenchley

A stained glass window at Holy Trinity Church, Fortitude Valley, remember parishioner and martyr Margery Brenchley

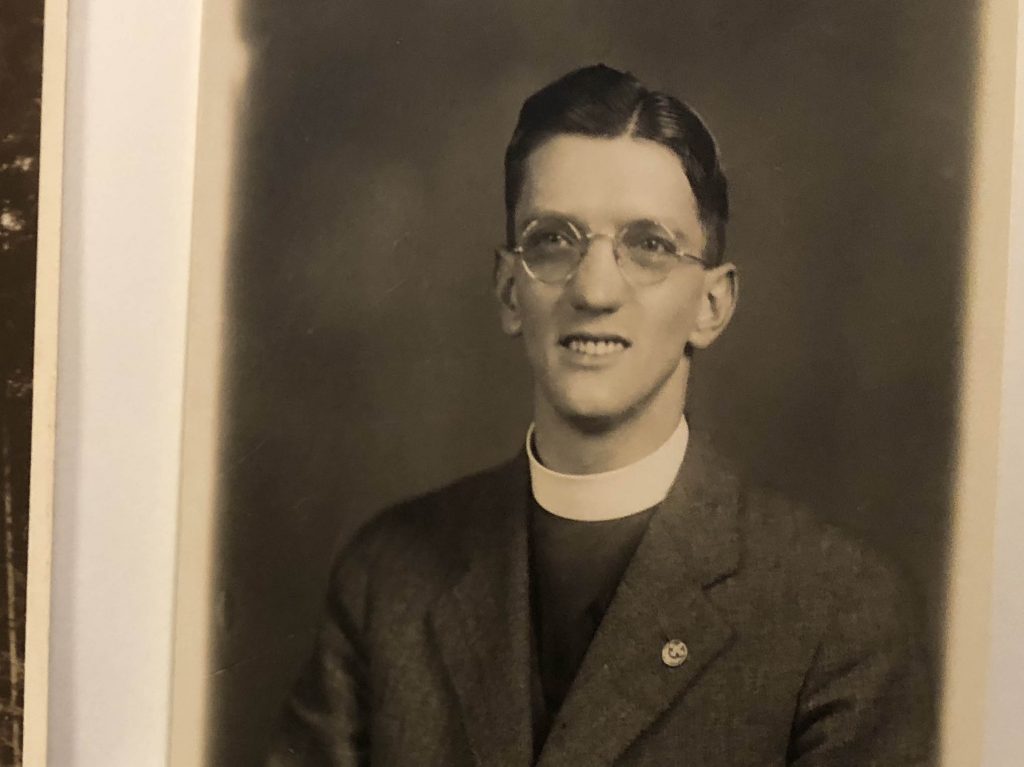

The most well-chronicled of the 12 missionaries, the pipe-smoking and bespectacled The Rev’d Vivian Redlich, hailed originally from England. The son of a Church of England priest, he sailed to Australia to work in the Rockhampton Diocese from 1935 to 1940 as part of the Bush Brotherhood – missionaries who (according to the recruitment pitch of the day) could “ride like cowboys and preach like apostles” as they ministered to remote and rural communities around Queensland.

The Rev’d Vivian Redlich travelled to New Guinea via the Rockhampton Diocese

How and why the New Guinea Martyrs were murdered have become less significant over the decades – supplanted by the lasting tribute to their individual and collective faith and service to the church, God and the New Guinea villagers they lived among in east coast outposts such as Gona, Buna, Popondetta and Sangara.

The Anglican Church had first established missionary stations in New Guinea in 1891 and over the years – up to the outbreak of World War II – priests, teachers, nurses and other lay people volunteered to spend between months and years building Christian faith communities among the local tribes. And, yes, sorcerers, witchdoctors and headhunters still loomed large among the tribes by the 1940s.

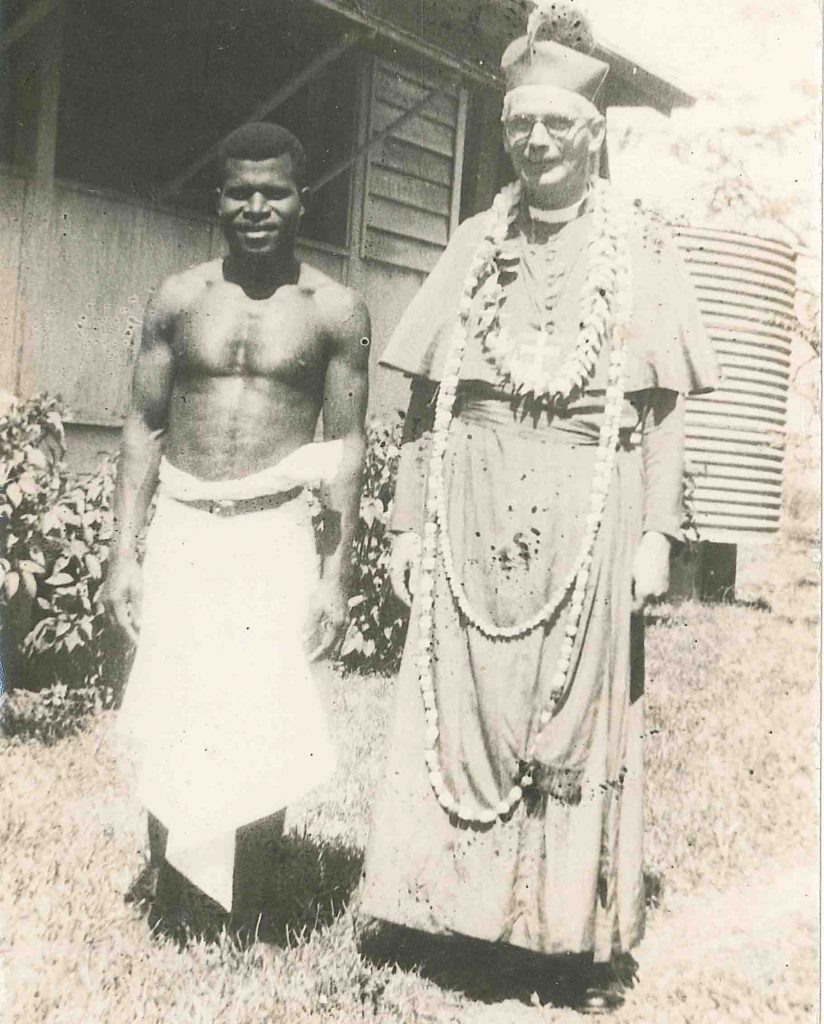

With the Japanese invasion seemingly inevitable by the start of 1942, the Bishop of New Guinea, The Right Rev’d Philip Strong, spoke to the disparate missionary stations via shortwave radio urging them to stay at their posts, despite the danger.

The Right Rev’d Philip Strong, army chaplain, Bishop of New Guinea and later Archbishop of Brisbane (Image courtesy of the Records and Archives Centre)

The Right Rev’d Philip Strong, army chaplain, Bishop of New Guinea and later Archbishop of Brisbane

“God expects this of us. The Church at home, which sent us out, will surely expect it of us. The Universal Church expects it. The tradition and history of missions requires it of us. Missionaries who have been faithful to the uttermost and are now at rest are surely expecting it of us. The people whom we serve expect it of us. We could never hold up our faces again, if, for our own safety, we all forsook Him and fled when the shadows of the Passion began to gather around Him in His Spiritual Body, the Church in Papua.”

Advertisement

While women missionaries were given the opportunity to leave, Miss Parkinson and nurse May Hayman, willingly stayed at their stations in Gona through much of the initial offshore conflict until Japanese troops began landing at the beach near their mission. They then escaped into the jungle, guided by Fr James Benson and several Australian and American servicemen, and spent several weeks in a life-and-death escape, wading through swamps, rivers and thick vegetation.

Eventually they were turned over to the Japanese military who tortured them for two days before bayonetting them and throwing their bodies into a shallow grave.

Mrs Mae Frame, great-niece, of martyr Mavis Parkinson, with students from Ipswich Girls Grammar School

Mrs Frame grew up with the story of Mavis Parkinson, an ever-present part of family life for her mother, Betty, Mavis’ sister.

“The story of Mavis Parkinson has been such a vital and important part of our family history and the history of St Paul’s, Ipswich and it has meant so much to Mavis’ descendants that the story of the New Guinea Martyrs, including Mavis, their memory and commitment to their faith and the bravery that they displayed during such dangerous times in World War II are celebrated by our local congregation,” Mrs Frame said.

Advertisement

“The church, parishioners and local schools – West Moreton Anglican College and Ipswich Girls Grammar School – are involved every year on Martyrs Day and the schools support it by sending students along who celebrate mass and help light candles to keep alive their memory.”

Many of the other martyrs were hunted down by Japanese soldiers and beheaded on the beach at Buna, with accounts of most of the martyrs’ deaths emerging months later from local eyewitnesses or from the Japanese military after their defeat and retreat from New Guinea.

The Rev’d Redlich was also murdered by Papuans – although mystery and misinformation surrounded the Englishman’s death for almost 70 years.

His was a tragic story on so many levels as he had met and fallen in love with the mission nurse who cared for him during illness – May Hayman, originally from Adelaide.

The Rev’d Redlich and nurse May Hayman had only become engaged in New Guinea just weeks before the ensuing chaos, death and destruction of the Japanese invasion. The pair worked at different mission stations about 40km apart, and The Rev’d Redlich was on his way to rescue his fiancée when he was entrapped on a jungle track by six Orokaivan tribesmen armed with spears.

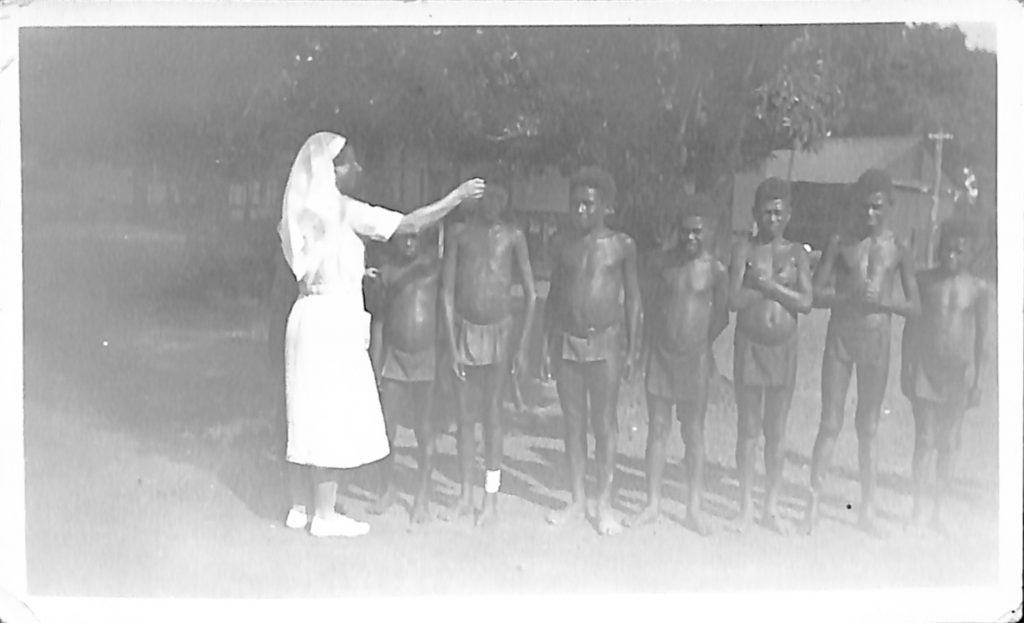

Nurse May Hayman administers cod liver oil medicine to villagers at Dogura, New Guinea (Image courtesy of the Records and Archives Centre)

It was believed that The Rev’d Redlich was among the martyrs beheaded on Buna Beach. But decades of secrecy among the villagers around Popondetta began slowly lifting from 2005 to 2009 when the truth of the murder by local villagers was confirmed.

It culminated in The Rev’d Redlich’s only surviving descendant, Pat Redlich, a parishioner at St Matthew’s Anglican Church, West Pennant Hills in Sydney, travelling to PNG in 2009 for a forgiveness and reconciliation ceremony, which finally lifted “the curse” that local villagers had believed existed since the 1942 murder.

A central and remarkable figure in the whole New Guinea Martyrs story was Bishop Strong, who spent 26 years as Bishop of New Guinea before becoming Archbishop of Brisbane in 1962.

He was the instigator of New Guinea Martyrs Day. Having written personal and moving letters to the families of the murdered martyrs in the harrowing months that followed news of the deaths of the 12 staff and clergy from the Anglican missions, Bishop Strong announced in 1947, after a Sacred Synod in the New Guinea Diocese, that the missionaries would be commemorated on New Guinea Martyrs Day.

St Paul’s, Ipswich priest The Rev’d Steve McMahon and over 120 parishioners celebrated New Guinea Martyrs Day by lighting 12 candles, one for each martyr on Sunday 1 September

St Paul’s, Ipswich priest The Rev’d Steve McMahon and over 120 parishioners celebrated New Guinea Martyrs Day by lighting 12 candles, one for each martyr on Sunday 1 September

Executive Director of St Francis College, the Right Rev’d Dr Jonathan Holland has just written the complete biography of the former Brisbane Archbishop, titled The Destiny and Passion of Philip Nigel Warrington Strong.

Bishop Holland was approached to write the biography by Archbishop Strong’s literary executors several years ago. His research took him to many places in England where Strong lived, grew up and studied. He also ventured to PNG and vitally important places during his tenure as Bishop, especially Dogura where Strong oversaw the cathedral and mission centre.

“The book is important not only because it tells Strong’s story, which itself is quite an adventure, or because it chronicles the life and times of one of our Archbishops, but also because his life and that of many of his peers shines a light on a past age, its values and ways of thinking and asks us whether there is something in the way he and others of his generation chose to live that is worth recovering,” Bishop Holland said.

Anyone interested in ordering a copy of Bishop Holland’s book on Archbishop Strong, can contact him directly via email to jholland@anglicanchurchsq.org.au.